The recently concluded Digital Rights and Inclusion Forum (DRIF) brought together a diverse mix of stakeholders across the public and private sectors to promote digital ubuntu approaches to technology governance. As a first-time participant, I can confidently say it’s one of the most intentional and context-aware conferences on digital rights I’ve attended—and I’ve been to many.

In this recap, I highlight some of the most insightful and contextually relevant sessions, including the launch of the latest Londa Report. Against the backdrop of dwindling activism funding, particularly within digital rights spaces, timely conversations emerged around trust, privacy, surveillance, AI-driven governance, and the media’s shifting landscape under increasing conservatism. Hosted in partnership with the Zambian Ministry of Science and Technology, the event drew a cross-section of actors: INGOS like Wikimedia, Big Tech, grassroots activists, policy advocates, and journalists from across Africa.

This article focuses on six sessions that stood out, exploring regional policy on data governance, digital kinship in elections, technology for harm reduction, AI and social trust, and sustainability strategies for grassroots civil society organizations. These insights are especially relevant to our stakeholders at CcHUB’s Technology & Society Practice.

Implementing the AU Data Policy Framework

In a multi-stakeholder dialogue hosted by KICTANet and Zambia’s Data Protection Commissioner, participants explored the implementation realities of the African Union (AU) Data Policy Framework, adopted in 2022. The Framework aims to harmonize data governance across the continent while balancing open data flows with the protection of individual rights; critical for a trusted, inclusive digital economy.

Although member states have been slow to ratify the framework, countries like Zambia are progressing through donor-supported infrastructure. This raised critical questions about ownership: can local policy truly be considered local if it relies heavily on external technical support? Officials emphasized that the design process was collaborative and led by Zambians, with donors offering strategic—not directive—input.

The session underscored the need for the AU to lead ratification efforts through defined timelines and accountability structures. As the Commissioner noted, citizens must be seen as active participants in the data ecosystem, not just passive users. For policy to shape a meaningful privacy culture, citizens must understand their ownership of data and policymakers must craft context-driven, enforceable governance.

Digital Kinship and Elections

Digital kinship describes how community, identity, and care are built and maintained through digital means. In Africa, where elections are both political and deeply social events, digital kinship becomes a vital lens through which we understand electoral participation, activism, and solidarity.

This session, led by the African Internet Rights Alliance, delved into how echo chambers, algorithmic amplification of polarisation, and platform governance affect cross-border solidarity during elections. One panelist, a public policy lawyer, traced the rise of separatist narratives to the pandemic-era reliance on digital spaces, noting how these patterns bled into offline interactions.

The conversation then turned to the risks posed by deepfakes, AI-generated disinformation, and the structural unaccountability of social media platforms—especially regarding labour practices and content moderation in Africa. Attendees emphasized the need for Africa-specific platform accountability, rooted in local experiences rather than borrowed standards from the Global North.

A key takeaway was the need to shift our civic engagement from episodic election-year enthusiasm to sustained, everyday accountability. Stronger digital kinship can support this shift, fostering solidarity, increasing transparency, and demanding better governance.

Technology-Facilitated Violence: Women in Protection

I attended four sessions focused on reducing gender-based violence through tech solutions. A clear pattern emerged: women were leading conversations on solutions—helplines, apps, collaborative policy frameworks—while technical discussions on harm (AI, moderation systems, platform risks) were male-dominated. This imbalance risks perpetuating advocacy silos.

A standout session introduced the Safecity App, a crowdsourced platform originally developed in India and now adapted for parts of Africa. It allows survivors to report harassment anonymously, generating geotagged heatmaps that guide community action and policy advocacy.

Safecity reduces TFGBV by making incidents visible, anonymous, and actionable. Its survivor-centred, open-source approach empowers youth groups, women-led organizations, and policymakers to design localised interventions. In Kenya, feminist community leaders leveraged the data to collaborate with law enforcement, achieving both judicial and community-led outcomes.

In a continent where digital violence disproportionately silences women and marginalised groups, Safecity’s model represents a scalable, locally adaptable approach to restoring safety and voice.

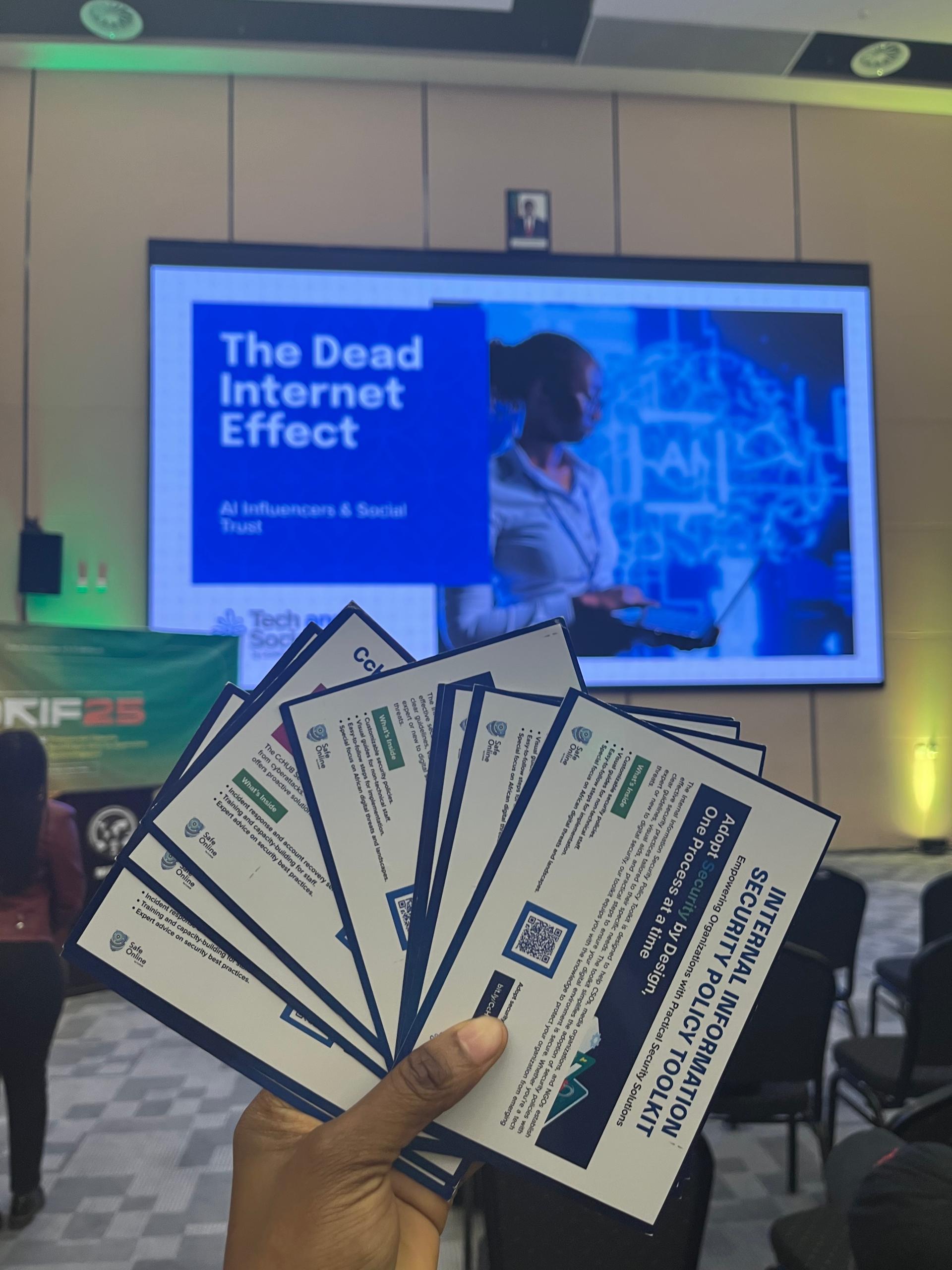

AI Personas, Content Moderation and Social Trust

In my lightning talk, I explored the emerging trend of AI-generated personas—synthetic influencers capable of shaping public opinion in subtle, persistent ways. We examined the implications of AI influencers replacing human creators in online discourse and public debate.

The discussion covered the risks: disinformation, erosion of authenticity, privacy violations, and threats to freedom of expression, especially in politically sensitive contexts. Vulnerable groups like journalists and activists face heightened risk from AI deception and content manipulation.

The discussion covered the risks: disinformation, erosion of authenticity, privacy violations, and threats to freedom of expression, especially in politically sensitive contexts. Vulnerable groups like journalists and activists face heightened risk from AI deception and content manipulation.

While the current wave of AI influencers seems largely focused on American pop culture and self-help niches, the broader implications for African political discourse are concerning. The session called for AI regulation, stronger trust frameworks, and public digital literacy to ensure ethical use of these technologies.

To Fund or Decommission: Sustaining Activism in a Shrinking Civic Space

In this closing session, funders and digital rights advocates tackled one big question: how do we sustain digital rights work amid shrinking civic space and declining donor funding?

With traditional funding sources like USAID scaling down, funders emphasized the importance of strategic alignment and coalition-building. A compelling question was raised about the visibility of African philanthropists. In response, the African Philanthropy Forum clarified that many fund locally—just often anonymously and via intermediary funds.

Attendees were introduced to StartPointAfrica.org, a new platform that connects African philanthropists and diaspora donors with vetted civil society organizations.

Activists were also encouraged to seek collaborative grants, co-design with communities, and position themselves within broader digital governance trends to unlock new funding pathways.

The Time to Act Is Now

DRIF25 made one thing clear: Africa is not short on ideas or solutions. From the AU Data Policy Framework to community-led innovations like Safecity, we already have the tools and knowledge to shape a future where digital rights are protected, ethical AI is prioritised, and no one is left behind. What’s missing is the level of investment needed to scale these efforts.

We call on funders in the digital rights and inclusion space to go beyond interest and commit resources to African-led solutions. The data has been gathered. The gaps have been identified. Organizations like Paradigm Initiative have outlined clear, actionable recommendations. What’s needed now is the will to act.

At the same time, African governments and institutions must take responsibility for implementing our own policies. We cannot continue to look outward for leadership on matters that deeply affect our people. The success of digital transformation on the continent depends on our willingness to lead with context, act with urgency, and invest in our own potential. The time to act is now—on our terms, for our future.