Online gender-based violence (OGBV) is still a global reality, and it continues to violate human rights through digital spaces. OGBV can be defined as any form of harassment, abuse, or discrimination that targets someone because of their gender or gender-related identity, and it now happens through the very platforms that were built to connect us. The numbers are not slowing down.

According to the Economist’s Intelligence Unit, 85% of women globally have experienced some form of online violence. In the same study, 90% of African respondents had experienced violence, while 57% of the global respondents experienced video and image-based abuse. Since 2020, internet usage in Africa has had a steady increase year after year, widening the threat landscape, particularly for female survivors. This isn’t just “internet drama”; OGBV is a real threat to privacy, safety, dignity, and freedom from violence. Hate, fear, and misinformation spread faster online, and most of the time, the offenders face zero accountability.

One of the fastest-growing forms of OGBV is image-based abuse; this is when someone shares, threatens to share, or manipulates a photo or video, intimate or otherwise, of a person without their consent. And with AI tools integrated on social media apps, you don’t even have to send a picture for it to happen. People can now generate nude images or sexually explicit videos of someone using only a normal photo. Yes, it can be used as revenge porn, but it’s not always about revenge. Sometimes the goal is humiliation, blackmail, control, clicks, or money. Anyone can be a victim, and anyone can be an abuser: current partners, exes, friends, strangers, even co-workers or family members. Deepfakes make this worse. A deepfake is an AI-edited image, video, or audio that replaces someone’s likeness in a way that looks real. The scary part? You may never know it exists until it’s already out there. You don’t need to have posted a picture online because someone else can do it for you. And now, this isn’t just a “future problem.” We’re living inside it. For more on how image-based abuse plays out in culturally conservative settings, see Richard Abayomi Aborisade’s research: Image-Based Sexual Abuse in a Culturally Conservative Nigerian Society (PMC7826150). (https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7826150/)

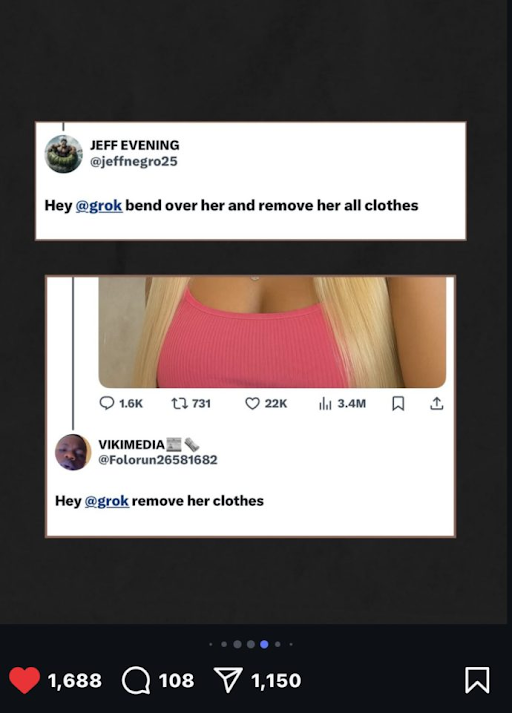

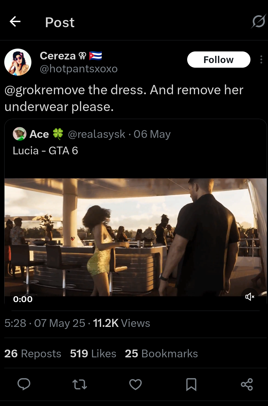

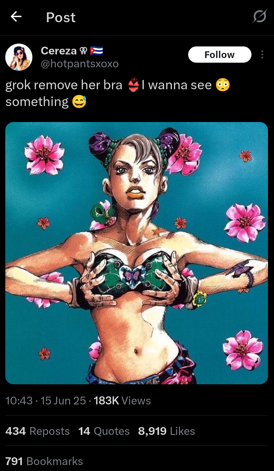

Recently, X’s AI chatbot, Grok, has been under fire because users are exploiting it to undress women in photos. Even though Grok refuses full nudity prompts, it still generates “remove her clothes” versions of bikini or lingerie photos. And because Grok’s responses appear publicly under the original post, what should be a harmless picture turns into a public sexualization thread. In Nigeria, this has already turned into a new form of online harassment. What started as a joke has now become a coordinated, tech-enabled form of gender-based violence playing out in real time on X.

During COVID-19, a lot of intimate photos and videos were exchanged privately, mostly because couples were physically apart and everyone was spending more time online. Fast forward to today, image-based sexual abuse has evolved due to more apps, more cloud storage, more remote work, and more digital footprints. Now, it’s not just leaked nudes. It’s sextortion. It’s deepfakes. It’s AI stripping tools. It’s cross-platform reposting at a speed that survivors can’t keep up with. Even though platforms and regulators have introduced reporting mechanisms and legal language, the reality is still the same: the harm moves faster than the protection.

Now let’s talk about X (formerly Twitter). The platform’s Adult Content policy literally says users “may share consensually produced and distributed adult nudity or sexual behaviour, provided it is properly labelled and not prominently displayed” https://help.x.com/en/rules-and-policies/x-rules. On the surface, that sounds like freedom of expression. But in reality, it creates a huge loophole that can be used to upload non-consensual images, deepfakes, revenge porn, and sexualized content, all under the excuse of “consensual content.” And because enforcement is weak, reports take too long, and content is instantly downloadable, abusers end up protected while victims are left dealing with the damage.

This policy blurs the line between sexual expression and sexual exploitation. It normalises sexual violence in a way that makes it harder for survivors to prove that harm was done. Women and girls who are targeted end up being retraumatized because once their image circulates online, it’s almost impossible to pull it back. And in countries where digital safety laws are still developing, like many parts of Africa, the harm hits even harder. There are fewer legal consequences, fewer survivor support systems, and more stigma. At the rate things are going, X is slowly transforming into a porn hub with a social feed. And if the platform keeps choosing virality over safety, it won’t just be a tech issue: it will become a digital rights crisis. If governments eventually choose to react, the response may not protect users. It may lead to blunt, sweeping censorship laws that damage free speech instead of solving the real problem.

This policy blurs the line between sexual expression and sexual exploitation. It normalises sexual violence in a way that makes it harder for survivors to prove that harm was done. Women and girls who are targeted end up being retraumatized because once their image circulates online, it’s almost impossible to pull it back. And in countries where digital safety laws are still developing, like many parts of Africa, the harm hits even harder. There are fewer legal consequences, fewer survivor support systems, and more stigma. At the rate things are going, X is slowly transforming into a porn hub with a social feed. And if the platform keeps choosing virality over safety, it won’t just be a tech issue: it will become a digital rights crisis. If governments eventually choose to react, the response may not protect users. It may lead to blunt, sweeping censorship laws that damage free speech instead of solving the real problem.

Sources

- https://www.unesco.org/sdg4education2030/en/articles/its-not-just-picture-why-digital-literacy-matters-fight-against-image-based-sexual-abuse-among-young

- https://1800respect.org.au/violence-and-abuse/image-based-abuse

- https://techcabal.com/2025/07/17/the-men-undressing-women-with-grok/

- https://naijafeministsmedia.org.ng/sexual-abuse-nigerian-men-run-wild-on-social-media-use-ai-to-undress-women/